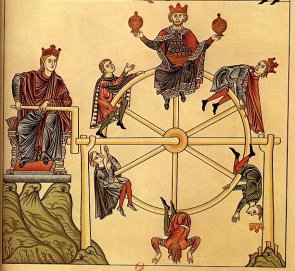

The Wheel of Fortune, Hortus Deliciarum, copy of miniature from Manuscript by Herrad of Landsburg (1130-1195), Hohenburg Abbey, Alsace.

This semi-academic book, published by Peter Turchin and Sergey A. Nefedov in 2009, is on the topic of how societal structures and population interact. The title SECULAR CYCLES refers to demographic cycles lasting a minimum of a century.

CHAPTER 1, the introduction and most interesting chapter, briefly fills in the background of the subject, covering earlier theories ranging from the simple Malthusian conjecture concerning population and resources, through Monetarist theories, to Marxist thought on the matter; each receives criticism, mostly in the realm of their failures to explain the data as it is understood. It establishes some of the key concepts and terminology used by academics, problems with data collection and the importance of distinguishing raw data from trends. Careful consideration of this area will prove key to novice readers such as myself.

Structural-demographic theory is then defined:

In this book we examine the hypothesis that secular cycles – demographic-social-political oscillations of very long period (centuries long) – are the rule rather than the exception in large agrarian states and empires.

The demographic portion of the theory draws heavily on Malthusian theory, introducing important concepts such as carrying capacity, resources, etc. The social portion defines elites (the owner of rents) vs commoners (payers of rents), and how the former extract resources from the latter. The political portion of the theory concerns the actions of the State, which appears to be the important contribution of the authors. The State provides, or fails to provide depending on its health, law & order as well as other services, such as public health and (unmentioned, I think) currency support, an important part of a healthy economy.

From here we progress to the two phases of the cycles.

In the integrative phase, particularly the first segment or subphase, the commoner (peasants, serfs, or whatever the local term might be) population is growing, the elite population is relatively small and unified, and the State is more in less in agreement with the elites, strong, and effective in its putative tasks of maintaining order. External, successful wars are not inconsistent with this phase, especially if they add territory into which the expanding population may move, thus relieving pressures which will lead to the second phase, below. The economy is perking along, often resulting in a period characterized as a Golden Age in retrospect. But as the integrative phase grows long in the tooth, overpopulation, defined in the context of carrying capacity of the land, forces the per capita (or per household) income of the commoners downward, while prices increase. During this stagflation subphase, the elites enjoy their Golden Age and, crucially, their numbers increase beyond reason.

The disintegrative phase’s beginning is marked by one or more crises of either exogenous or endogenous source. Commoner populations decline precipitously from either migration or mortality, and the elites enter crisis as their true basis of wealth, the commoners, suddenly decrease in number. The elite crisis results in the depression subphase, marked by often extended, vicious civil wars. The violence discourages the commoners from basic economic activity, thus depressing replacement rates of commoners, while elites are busy exterminating themselves. The State is often broke and unstable, and sometimes in danger of being captured by the elites. The depression subphase often lasts several generations, until the elites become tired of the warring and dying, and have been reduced to a more reasonable number. The peace permits the commoners to venture forth from their sanctuaries, grow food, and raise their replacement rate, marking the beginning of the integrative phase of the next secular cycle.

To say Chapter 1 is the most interesting is not to denigrate the following chapters. I had envisioned these sections, which are case studies of how well structural-demographic theory fits the data available, to be dry and boring. To the extent possible, however, Turchin and Nefedov’s presentation is interesting, using proxies where raw data is not available, such as the temporal distribution of coin hoards or indictments for infanticide, and referring to lurid episodes (assassinations, massacres) from time to time. Both spark the imagination!

King Edward II of England, hapless victim of demographics?

The case studies are of the Plantagenet and Tudor-Stuart periods of England, the Capetian and Valois periods of France, the Republican and Principate periods of Rome, and the Muscovy and Romanov periods of Russian history. Since I’m neither a historian nor an avid reader of any of these particular historical subjects, these were relatively new to me, and thus interesting.

My Takeaways

As a reminder, this book’s conclusions are confined to agrarian societies, defined as societies where at least 50% of the population is working the land, and often it’s a far higher percentage. Attempting to apply their conclusions to today’s societies is undoubtedly an error, but quite tempting.

Perhaps most salient for me is that the three population groups, commoners, elites, and State, have the same motivations – namely, to survive and prosper – but define survival in starkly different terms.

The commoner faces the existential problem, as they work the land, pay the taxes, face stark death if the crop fails, and a brooding future as their numbers increase.

The elite’s definition of survival is to continue within their social stratum, not just as individuals but as families or clans. To sink back to the commoner level is to fail, and many or even most were willing to risk their lives in military service or civil wars to retain their positions.

Those of the State, usually of a monarchical position, look to maintain their positions at the center of power. While certain of these are willing to accept a degradation of status in exchange for continued life, most persist until they are ended violently in the disintegrative phase.

This polymorphic definition but constant framework suggests the basic psychology, perhaps evolutionary psychology, which drives the secular demographic cycle in concert with the implacable realities of limited food sources, land arability, and organisms dependent on ingesting the former for continued existence while reproducing without concern for the future – for most organisms, a simple, untranscendable reality – has to do with the relative definition of survival. It would be interesting to examine how and if a nominally celibate religious option, such as joining the Catholic orders or certain Protestant religious groups, acts as a safety valve for population pressure.

Another thought that occurred to me has to do with proxies. While I enjoyed how they used proxy metrics to at least measure the dynamics of the important metrics, if not the raw values themselves, I was a little disappointed that they didn’t mention the potential logical fallacies involved. Perhaps they expect that the trained reader is well aware of them, but for my own edification I had to realize that a proxy may suffer from the logical fallacy of affirming the consequent. That is, a proxy is implicitly a statement that

if dv changes then pv changes in some predictable manner

where dv is the desired value of the target metric, pv is the proxy value in a related metric, and predictable manner means some function f can be applied to dv such that

f(dv) = pv

and f is a reversible function. That is, it’s not a trapdoor function in the sense that it’s not easily calculated in reverse – a simple example is the exponential function, f(x) = ax, where calculating the xth root of some value is not nearly as simple as calculating the exponential value. The usefulness of a proxy value correlates directly to how easily the transformation function f(dv) can be reversed into a function g such that

g(pv) = dv

I’m a little off point here, so the fallacy which worries me is that it’s difficult to prove that the relation between a desired value and/or its dynamics and a proxy value and/or its dynamics for a desired measurement is an if and only if statement, and if it’s not, then it’s possible some independent, and uninteresting value, may be moving that proxy value. For example, at one point Turchin and Nefedov use the recorded heights of military recruits as a proxy for measurement of the available food rations. But what if a new religious cult has come into vogue that forbids consumption of certain foodstuffs containing the nutrients which boost people’s heights? Using this simple proxy may seem to show oncoming famine, when in reality it was simply a cult becoming popular.

That’s just something to keep in mind, especially for the untrained reader, like myself.

Conclusions

I dove into this book in the belief that demographics are, as ever, humanity’s future, and I came out of it with that belief only bolstered. The details of how the demographics change, even if confined to agrarian societies, was fascinating and instructive in suggesting that the evolutionary survival strategy of boundless reproduction appears to lead inevitably to the human tragedies of war, famine, and disease.

War is the fierce battle over resources as they become scarce relative to the number of people demanding them, whether they be for survival or for maintenance of societal position.

Famine comes when that battle over resources actually blots out those very resources over which the battle began, or when exogenuous factors, such as climate change (think of a super-volcano explosion cooling the world’s atmosphere into a mini-Ice Age).

And disease often ravages us when our numbers grow to the point where we’re too crowded and our medical knowledge cannot compensate.

If this is a subject of interest to you, it’s worth a read.

Recommended.